“Faggot! Ew, that’s so gay!” I remember the way other third graders used those words to insult each other on the playground. I thought of my family’s trip to New Jersey the previous weekend. The woman my mom had kissed. When I spoke up about how ignorantly the playground kids were using that language, they teased me. My mom told me later that night, “It’s OK, love them more, we don’t know what they are going through.” This was and continues to be my truth. To love them more.

I came to embrace this truth through my mother. When I was younger she brought me to death penalty rallies and vigils. We would chant, sing and chant some more: “Break the needle, smash the chair, Maryland’s death penalty is unfair.” The people surrounding me shared my truth; I learned from them that everyone deserves a second chance, that murderers are people, too. That even they deserve someone to love them more. This same truth applies on a smaller scale. Forgiving someone who mistreats you, responding with kindness, loving them more.

This can be hard considering our society teaches young men like me to shut down our emotions. We are taught to hate our enemies, to fight with each other, to be aggressive, instead of loving. We see this on our TV shows, in our movies, in our music, and even in our books. Men are strong providers who must save damsels in distress. In “The Boy Who Drew Monsters,” Holly thinks, “Tim should be out here in the cold, protecting them,” (Donohue 35). Male artists like Kanye and Chief Keef reflect their anger and the violence they have witnessed in songs that spread the message of violence and aggression.

We forget the teachings of Gandhi, Mandela, and King. Aggression leads to conflict, crime, and stubbornness. It’s a reason Washington is so divided, a reason police shoot unarmed black teens, a reason “rough rides” are still legal. We can’t see past what others do wrong. We respond to hate with hate, when we need to respond with love.

Last year, riots shook our city after Freddie Gray’s death. The images of Gray pleading with the cops, kids my age looting, and cars on fire haunted me. I tried and tried to understand how our city could be so divided. I easily understood why people rioted against systemic racism and militarized policing, but I couldn’t put myself in the police officer’s’ shoes.

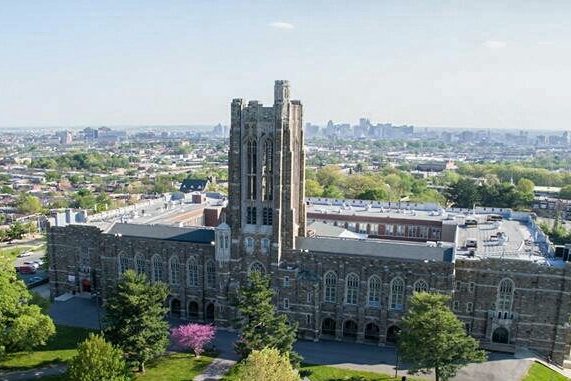

Later I would march with Digital Harbor students, neighbors, our councilman, and Wale (the “Ride Out” rapper). United, we chanted, “We Love Baltimore.” A #BlackLivesMatter sign in one hand, my other arm linked with a stranger, I walked past the National Guard, armed with intimidating guns. At that moment, I noticed that the people around me–black and white, young and old, of all different backgrounds–were all using love to heal our city. We were loving the officers who killed Gray, the people who destroyed businesses, the people who tore apart the city. We were bringing light to injustice and spreading a message of peace and love.

On our way back we met some teenagers who were interested in my sign. They challenged that a rally could make a difference. My mom asked them to share why. At the end of this encounter, which ended up lasting forty-five minutes, one of them said, “I wish more people took the time to listen like you.” By caring enough to listen, we had made a small positive impact on the world. This is the power of “lov[ing] them more,” even if they challenge you and your actions.

I knew that night that I was going to make it my mission to love everyone more, to support the oppressed and the disenfranchised, to bring peace and stability to our world. This has led me to volunteer for two political campaigns, and to aspire to be an activist or diplomat. I embrace loving them more as my truth. I wish that more people would do the same, to create a world of stability and kindness– a world free of injustice and hate.