|

A few dozen adults on two continents made this year's prize possible. Special thanks to:

Baltimore City College Teachers and Staff Amy Sampson Lena Tashjian Mark Miazga Alexander Best Patrick Daniels Sarah Jeanblanc Mark King Tonya Luster Rebecca Penniman Amber Phelps Principal Cindy Harcum Judges Ann Bacon Perry Bacon Charles Beckman Marion Bernstein James Blachly Rebecca Blachly Ari Bloomekatz Sharon Carney Michael Cross-Barnet Rebecca Cullen David Dudley Janae Eason Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson Lee Gardner Mackenzie Howard Lisa Kane Lawrence Lanahan Amy Lazarus Shelly Lazarus Brynna Leslie Whitney Levandusky Sara Lipka Bret McCabe Jennifer Mendelsohn Lalita Noronha Greg Ó Ceallaigh Odi Maraizu Onyenaka Cheryl Pruce Molly Rath Matt Rogers Julie Scharper Angela Shaeffer Geoff Shannon Jimmy Soni Martine Spinks Michael Tager Erica Whorley Gregg Wilhelm Mary Wiltenburg Baynard Woods Nicole Yeftich Writing Consultants Charles Beckman David Dudley Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson Lee Gardner Patrice Hutton Lawrence Lanahan Whitney Levandusky Bret McCabe Molly Rath Julie Scharper Geoff Shannon Gregg Wilhelm In my opinion, the Baldwin Prize’s biggest prize is insight and development. Each year, the prompt asks students to investigate some element of their intellectual and emotional life and reflect on what this personal truth says about the way we should all treat each other. The results of that process are often inspirational.

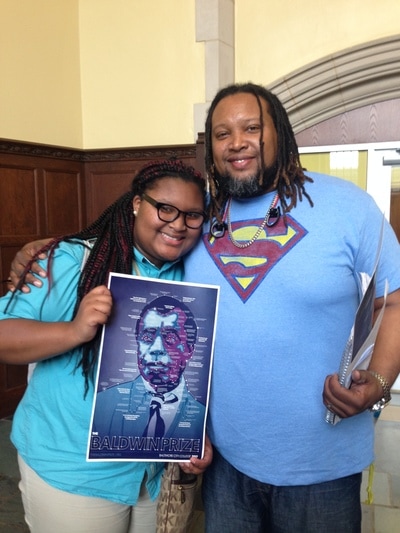

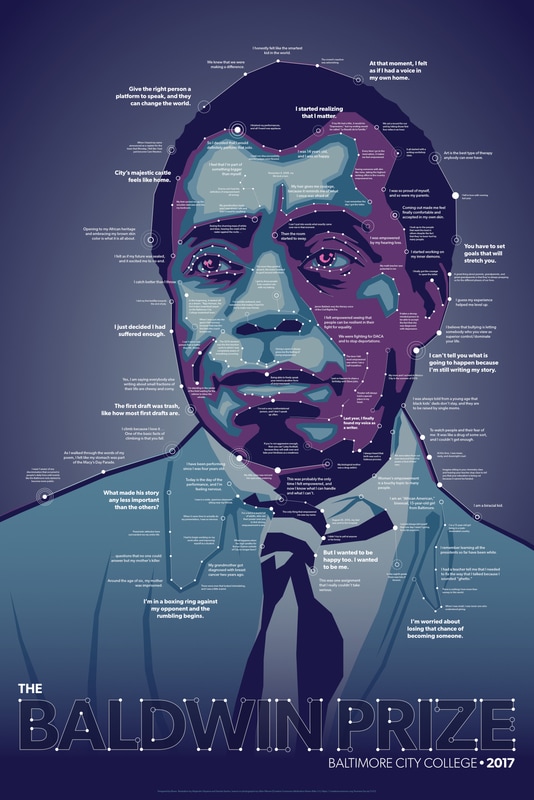

So writing, rewriting, talking about the prompt, and sharing an essay with others can be immensely rewarding. But this is also a competition, and only two of the many entrants will win a trophy and education grant. To give students a better sense of what their collective efforts looked like and something to commemorate what each of them accomplished, I commissioned a poster that incorporates one line from every essay that was entered this year. (One hundred and eight essays are represented here. One late entry was not submitted in time to be included.) That's the poster you see above. Our theme was empowerment, so a lot of students drew from challenging moments in their lives. There are epiphanies (“But I wanted to be happy too. I wanted to be me.”), confessions (“To watch people and their fear of me: It was like a drug of some sort …") and triumphs (“I finished my performances, and all I heard was applause.”). Brilliant team members at the firm Bivee designed the poster. Alexandre Siqueira illustrated it, inspired by two photographs of James Baldwin by Allan Warren made available under a Creative Commons license. I cannot thank Bivee and Alexandre enough for everything they put into this. You are welcome to print your own copy of the poster. Send me a message using the contact form, and I’ll respond with a link to a high-resolution file. This year, we split the Baldwin Prize into two divisions, one for freshmen and sophomores and another for juniors and seniors. One winner was selected from each division. Rachel Fink took the freshman/sophomore prize. Her winning essay is below.

The theme was empowerment. All students responded to the following prompt: Describe a moment when you felt empowered. This could have arisen from a single event or an ongoing activity. It could be in any setting--social, professional, academic. Why did you feel empowered? What did you do with that power? Did you use it responsibly? For a kid in a world full of adults, who use their power over you to feel strong, empowerment is rare. Any attempt at self-expression or empowerment is futile against the condescension and belittlement that will be thrown at you due to the ageism that marks your opinion as less than. Not to mention that if you work up the nerve and confidence to challenge this, you will generally be written off as a teenager acting out. This demeaning attitude toward children is what caused a very empowering moment in my life: standing up to someone who thought my pants were more important than my education. Throughout my educational career, dress code has been law. If those overpriced, unattractive khakis don’t reach well beneath your fingertips, you shouldn’t be surprised when you are pulled out of class. In fact, I missed my very first high school class due to the fact that my shorts were a whole three inches above my knee caps. Several days later I found out that my friend was held in our assistant principal’s office for the entire day because her pants were ripped on the knees and neither of her parents could leave work to bring her new ones. Yes, she was held for seven hours in an office and was forced to miss every single class because there were rips in her pants. Needless to say, I have many issues with this story and the thousands like it throughout schools. First, I wanted to explore why these rules exist. Of course I’ve heard the opinion that uniforms prevent the bullying of a student who does not have access to fashionable or expensive clothes. While this is a valid concern, there is little to no evidence in bullying literature to prove that uniforms fix these problems. I have actually seen a kid be made fun of because people could see from his ripped uniform that he only had one, while a kid from a more affluent family would have several pairs. Aside from this view, I’ve hear the idea that a young girl must be dressed appropriately as to not distract her male counterparts. This argument entirely clarified for me that a boy’s ability to focus on his education, no longer distracted by my knees, is seen by many educators as being more important than my access to an education. Now having an understanding of this gender-based injustice, I was not happy about being pulled out of a particularly interesting seventh-grade algebra class to see the dean of students looking me up and down as if i should be ashamed. “Do you really think this is appropriate for school?” he asked, tilting his head in order to look at the back of my pants. I can say with absolute certainty that the majority of students in Baltimore City Public Schools have experienced this condescending and demeaning tone from an authority figure who really needs you to know that they are above you. And although I should have no reason to prove the decency of my outfit, I feel that it is helpful to note that I was wearing shorts that, although shorter than dress-code-length, were paired with ankle-length black leggings. “You can’t even see my legs,” I replied. “Why don’t we see where you fingertips go,” he said with a smirk that showed just how proud he was to attempt to humiliate a twelve-year-old. Upon straightening my arms, the shorts went to roughly the bottom of my thumb. “Well let’s go to my office and find some pants for you to change into.” “Can’t I just go back to class?” “Not out of uniform!” he retorted, looking at me as if I had made some outrageous suggestion. No longer wanting to normalize the idea of an “educator” denying a kid her class time, I decided to explain to him his incredibly flawed position. I began by asking how he could possibly call himself an educator when all I had ever really seen him accomplish was diminish the education of female students. I proceeded to ask what made him lose track of his educational intentions to the point that this was all he had accomplished. This, followed by the threats of my intentions to explain to my family and the rest of the school how he’d sexualized and objectified the body of a preteen lead to my triumphant release back to class. This experience had a big impact on my understanding of empowerment. The two of us, while both empowered, used this power in different ways. While he used his authority to try to push me down both in my studies and in my confidence, I stood up for myself. In this instance we demonstrate the ways in which power is not in and of itself great but is great in the ways with which it is used. This year, we split the Baldwin Prize into two divisions, one for freshmen and sophomores and another for juniors and seniors. One winner was selected from each division. Rashaad Johnson took the junior/senior prize. His winning essay is below.

The theme was empowerment. All students responded to the following prompt: Describe a moment when you felt empowered. This could have arisen from a single event or an ongoing activity. It could be in any setting--social, professional, academic. Why did you feel empowered? What did you do with that power? Did you use it responsibly? Ask a retro gamer to recall their most profound moment in gaming, and that person may fondly remember their glory days in the arcade. They may remember the dimly lit neon rooms, decorated with large crowds, that pleasant aroma of pizza and nachos, and the many arcade consoles brightening the room like the shinning stars that engulf the night. They may tell of the ever-enlarging crowd around them, gazing in awe as they topple high scores that once reigned supreme, in games like Pac Man, or how they defeated a plethora of challengers, one by one, in the rings of Street Fighter. Hordes of gamers would send heartfelt cheers of encouragement and passion, adding more pressure to the already excited aura in the room. The energy that they generated, the respect that they obtained as a result of their dedication. Ask that same person if they thought of using that vigor and set of skills in a career, of any kind, and they may yield a perplexed, anxious chuckle, as if saying, "Even if I did, what could I have done?" Rather than remain oblivious and wondering, I used my passion and talent for video games in order to break the social limits set on both gamers and myself, resulting in my newfound role as a leader. Now, before I keep going, I am well aware of the hordes of stereotypes of gamers, including, but most certainly not limited to the "couch potato", the "violent antisocial kid", and the "lazy, attention deficit kid" clichès. I have heard them all and may likely continue to hear them constantly, like a broken record. But while the arguments have an iota of merit, they, on a much grander scale, are simply false. In fact, by delving into the world of gaming, I learned the trade of the gaming industry, including game design, game development, creative writing, and visual arts. I have also learned life lessons, such as teamwork, communication, and dedication. I laid the path of leadership in my freshman year of high school. As I was rather timid and soft-spoken, and isolated myself from others, I would never had thought that I would change Baltimore's City College for the better. Though meant in jest, I had an itching thought to establish a video game club, the first one, in fact, as City never officially had one. When I realized just how monumental my idea became, however, it took no time at all for me to start breaking ground. I had decided that I wanted to create a video game club, where I would not only play video games, but also create them, compete in tournaments, blog about them, and even host workshops on events in the gaming industry. The goal was to create a league of gamers, who could appreciate the values found within the gaming world, both as players, and as developers. In fact, while most clubs take about a month or two on average to set up, it took me only two weeks. Once I have an idea, not even Sonic could beat me in a race against time. Once I had my documents drafted and signed and my advisor selected, I only needed to gather members. Yet therein lies the problem. I wasn't exactly as iconic and brave as the many protagonists of my games, so it was a struggle to make my presence known. To make matters worse, some people, such as my peers and teachers, only knew how to belittle and ridicule my efforts. Still, it wasn't all terrible. After all, nothing is without its pros and cons. Their doubt only increased my faith, and after all the trials and tribulations, I would become the founder and CEO of City's first video game club as a sophomore. I also had to give it a name, of course, so after all the careful consideration, I chose a fitting name for it: Tech Knights, merging our profession with the mascot. Of course, any honorific comes with its struggles, with mine coming in the form of saboteur and treachery. For starters, I did gain a large quantity of members, fifteen seniors in fact, who were surprised that a freshman created a club period. Such tasks were usually left for sophomores. I was honored to see my work praised, and by my upperclassmen to boot, and I vowed to not let their faith go misplaced. I had to balance my time between being king of Tech Knights and pawn of the chess club. Puns aside, my coach soon became cross with me, as I wasn't fully devoted to chess, almost seemingly jealous at the fact, telling me that chess was more important. Finally, he had enough, but rather than making me choose between the two, he wanted me to endorse the chess team in my club. I was furious, more so than the God of War. I adamantly refused, and I left the team for a time, an act that soon would haunt me. Soon after, he got my club shut down, and my advisor quit on me. But rather than feel more trapped than a certain pink-dressed, blonde gaming princess, I worked on finding a whole new advisor and set of members, which I did successfully. To this day, Tech Knights is still functioning, and well to boot, and will continue to do so in the future. There's a difference between being a leader and a manager. Only the latter is made on an assembly line. The former actually takes real effort to work on. A leader is dependable, strong, courageous, accepting, and, above all else, simply that, a leader. Leaders don't have to remind others of their worth, because everyone, the leader included, respects them. A leader does not jealously compete with others. They aid them in order to help people become stronger. I did this and more, and that's what empowers me most. I guess my experience helped me level up. Below is the text of the speech that opened this year's awards ceremony.

Good afternoon, everyone. My name is Lionel Foster. I’m a City College graduate from the class of 1998 and the founder of the Baldwin Prize. Two years ago, someone decided to induct me into City College’s Hall of Fame. I didn’t think I’d earned that, but it wasn’t my choice. To give back and to make myself feel a little better about the tremendous honor, I decided to start a developmental and growth exercise disguised as a writing competition. Writing is hard. To do it well, you have to look squarely at yourself and take in the good and the bad. It forces you to be honest. That honesty can lead to humility and humility to kindness. You look within, and, hopefully, that insight affects the way you navigate the world and treat other people. I cannot name another writer who exemplified this traveling back and forth between the inner and outer worlds more than James Baldwin. This was a gay, black man in a country that tried to convince him he was worthless, who had the audacity to believe that what was true for him and about him had some bearing on how we all should conduct ourselves—how we should love, what we should fight over, and the unfinished country we might build together. He did all that with words, and I wanted to encourage high-schoolers at a pivotal moment of their development to do the same. We had 109 entries this year. We asked the essayists to write about a moment when they felt empowered. Some of you told me face to face when I spoke with your classes back in January that you’d never felt empowered. You knew what the word meant, but you thought it didn’t apply to you. That floored me, because it’s tragic, if you really believe you have no power. But what’s wonderful is having the opportunity, the support, and the occasion to put pen to paper and interrogate key moments in your life and see that you needed some amount of power just to survive this long. It was there. You just didn’t know it. Some of you wrote about the rush of performing in front of an audience, others about getting some glimpse of what you were meant to do with your life. And some of you wrote about tragedy—the death of a parent, the slow death of a loved one due to substance abuse, cancer, violence, depression, despair. You have seen so much. I consider it a breach of a social contract, of an unwritten agreement between generations like mine and yours that we have not protected you from so much of this. It pains me that I cannot bring a father back from prison or make it so that there’s no need for you to protest racism, misogyny, or ignorance. But we are creating a community where you can confront all of those things through the written word with patience, intelligence, and heart. So keep writing, and please know that you are loved. As far as I’m concerned, everything I and the many people who support this effort do is done to make it blindingly obvious that you are loved. Every word leads to that fact. So today we will hear briefly from all the students, announce the winners, eat, and celebrate. |

AuthorLionel Foster Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed